$60 million boost in Del. education funds sought for English learners, poor students

Gov. Carney wants Delaware's school districts to craft initiatives that benefit children who do poorly on state's standardized tests compared with children of means.

Listen 1:23

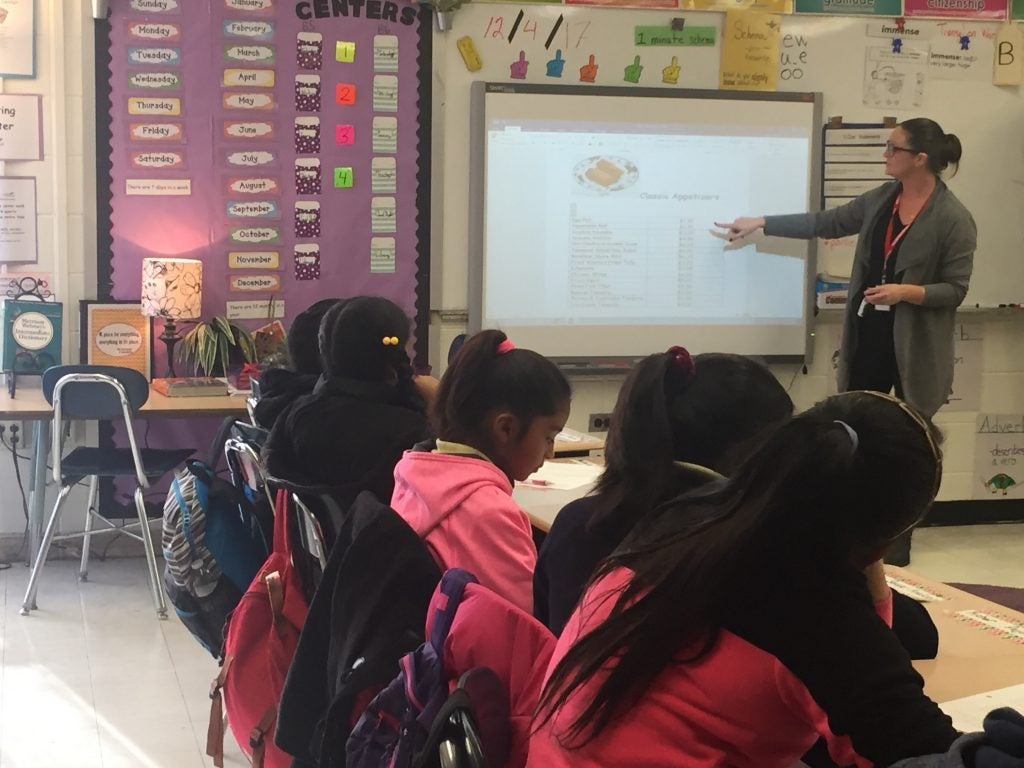

Delaware Gov. John Carney is proposing state funding to assist students learning English. (Rodel Foundation report)

Poor students and those learning English in Delaware would get about $60 million in new educational resources over the next three years under a plan proposed Tuesday by Gov. John Carney.

The proposal, which the governor will unveil this month in his budget proposal, would need approval by the General Assembly.

The “Opportunity Funding” initiative, if enacted, would give each of the state’s 19 public school districts a per-pupil allocation for each English learner and low-income student.

Currently, about 9 percent of the state’s 138,000 students had limited or no ability to comprehend, speak, write or read English when they enrolled. In addition, 35 percent of the students are classified as low-income.

Some schools have robust programs, such as the language immersion initiative at Lewis Elementary in Wilmington, where students — many of them Latino — spend half their days learning in English and the other half in Spanish. Last year a total of 26 elementary schools, plus two New Castle County charters. had similar immersion programs, a WHYY analysis found.

Under Carney’s proposal, however, all school districts would have money and flexibility to craft their own programs. The dollars could be spent to hire additional reading and math specialists, as well as counselors; expand trauma-informed training and after-school programming; and reduce class sizes. The state Department of Education must approve proposals.

The state also would work with educators, community advocates and parents to evaluate how the districts are using the money, as well as measure the progress of students.

Carney said he proposed the measure, in large part, because Delaware is one of only a handful of states that doesn’t target additional resources for kids who are poor and learning English. The American Civil Liberties Union is currently suing the state over its 80-year-old school funding formula, arguing that it deprives many children of their constitutional right to an adequate education.

“Despite the efforts of committed educators and school leaders, many of these students are not getting the education they deserve,’’ Carney said. “If we expect all Delaware children to have access to a world-class education, this is an issue that we can’t afford to ignore. Every child, regardless of their background, can learn and deserves every opportunity to succeed.”

Educators tout plan

Stephanie Ingram, president of the state teachers union, applauded Carney’s proposal.

“We know that children who are identified as low income or those who don’t speak English as their first language are more likely to have experienced trauma in their young lives or face unique challenges that need special attention from their educators,” Ingram said. “They need time with a teacher or a specialist to help navigate these challenges.”

Atnre Alleyne, a former state education official who runs the Delaware Campaign for Achievement Now that advocates for low-income children of color, stressed that the funding formula needs changes. But he called Carney’s proposal “welcome news and long overdue,’’ saying it “could make a real impact in our schools and classrooms’’ if lawmakers allocate the money not only for three years, but well into the future.

Heath Chasanov, superintendent of the Woodbridge School District, said he and other district leaders “appreciate the flexibility in program design that is being offered with this funding.”

Tony Allen, Delaware State University provost and chairman of the Wilmington Education Improvement Commission, said the proposal “is a signal to all that hoping and waiting for change is not a way forward for our children, and it hasn’t been for nearly three generations … It is a bold act, and, in my estimation, desperately needed.”

Educating low-income and English learners has been a challenge in Delaware. Since no state funding has been budgeted for English learners, districts must use local or federal dollars.

About 60 percent of the English learners are in programs that teach English as a second language, but those programs don’t’ require the teacher to be proficient in the student’s native language. Twenty percent of the English learners don’t receive any instruction in English beyond what other students receive, according to the nonprofit Rodel Foundation that researches the state’s education system.

Consequently, English learners perform well below native English speakers in state standardized tests. For example, in eighth-grade math, only 10 percent of English learners are proficient, compared with 40 percent of native English speakers.

In SAT tests in 2017, only 6 percent of English learners were proficient in reading/writing and less than 5 percent were proficient in math. By contrast, 54 percent of native English speakers met standards in reading/writing and 30 percent in math.

Low-income students also struggle to succeed academically in Delaware. In eighth-grade math, for example, 22 percent of low-income children were proficient, compared with 48 percent of children of means.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.