The Intrusion of White Families Into Bilingual Schools

Will the growing demand for multilingual early-childhood programs push out the students these programs were designed to serve?

Stephanie Lugardo’s second-grade classroom at Academia Antonia Alonso in Wilmington, Delaware, is bubbling. Students chatter with one another as they work, smiling and joking and wiggling in and out of their chairs. Sure—it’s an elementary-school classroom. It’s expected to exude the earnest joy of children growing into themselves. But this one is different. Smiles break out on an array of faces, and the chatter spills out in English and Spanish.

This is an incarnation of a new American pluralism, one of the latest iterations of Walt Whitman’s “teeming nation of nations” flowering in “their curiosity and welcome of novelty.” Downstairs, in a kindergarten class, an African American student exclaims to her friend, “I know how to say that in Spanish!”

José Aviles, the head of Academia Antonia Alonso, describes the school as a sort of multicultural nirvana. “We tell parents, ‘Your kid is going to be surrounded by Latino kids, white kids, African American kids—we offer everyone the same education, the same quality, the same love,’” he told me.

Academia Antonia Alonso, which opened as a public charter school in 2014, was designed to meet the needs of a linguistically diverse population. School leaders took full advantage of the flexibility allowed to charters to launch what’s known as a “dual-immersion” program: Children learn in both English and Spanish and, ideally, become fully bilingual in the process. The students switch languages each school day—if a class runs in English on Tuesday, it switches to Spanish on Wednesday. (With some exceptions: For example, all the school’s capoeira classes are usually in Spanish—with a smattering of Portuguese.) The program also balances the linguistic makeup of each class of students through its enrollment process. About a third of the school’s children are formally recognized as English learners (ELs), students who are still developing basic proficiency in that language. Nearly two-thirds of the school’s students are Latino, while around half of those enrolled are native Spanish speakers; the other half are native English speakers.

Dual-immersion classrooms aren’t just joyful to watch. They’re also ever more important to understand as their approach grows in popularity across the country. But there are some indications that multilingual schools’ increasing appeal is inadvertently undermining the original purpose for the model.

Dual-immersion programs seem like an answer to a range of difficult questions in education. For instance: How should U.S. schools educate their rapidly growing population of students who speak a language other than English at home? How can districts with shifting demographics simultaneously meet the needs of all of their students? How can schools prepare students for a complicated global economy (and convince families that they’re doing so)?

Research suggests that linguistically integrated dual-immersion programs work best for ELs. These “two-way” programs enroll roughly equal numbers of native English speakers and native speakers of the other language. And, of course, immersion programs offer the perk of multilingualism to all students regardless of what languages they speak at home.

It’s no wonder that new immersion programs are popping up faster than anyone can count (literally: there’s no up-to-date tally of the number of programs in the United States). In the past decade, Utah’s dual-immersion initiative covers around 200 schools. Delaware has a similar statewide program. Portland Public Schools in Oregon has doubled the size of its dual-immersion programs to more than 5,000 students in the past eight years, with those classrooms instructing in a combination of English and Spanish, Mandarin, Vietnamese, Russian, or Japanese. New York City recently launched dozens of new dual-immersion programs across a host of languages.

“We have an incredible wealth, a resource that comes into our country … [this] linguistic and cultural wealth and capital,” Michael Bacon, who oversees the dual-immersion programs in Portland, told me. “If we really, truly are reflective about our history and our country, if we want to stop the systems of repression, if we want to uplift our people and uplift our country, then I think [dual-immersion] is one of the best investments that any community, that any school system, can make.”

This isn’t a sui generis moment in U.S. language education. Multilingual instruction has a long history in American public schools. In the 19th and 20th centuries, immigrant communities speaking German, Italian, Spanish, Polish, Dutch, or other languages pushed, at various times, for their children to continue learning their parents’ native tongues even as they learn English.

English-speaking Americans’ discomfort with multilingual schools has a similarly long history. Various political pressures—anti-German sentiment during the World Wars, for example—chipped away at these programs over the years. In the 1990s, English-only advocates enacted mandates that largely eliminated bilingual education in California, Arizona, Massachusetts, and in districts around the country. Most of these were Spanish-English programs, which came under scrutiny as part of broader American anxiety about the unity of the country’s identity. Samuel P. Huntington, a political-science professor at Harvard, captured the mood in his 2004 book Who Are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity, warning, “Spanish is joining the language of Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Roosevelts, and Kennedys as the language of America. If this trend continues, the cultural division between Hispanics and Anglos will soon replace the racial division between blacks and whites as the most serious cleavage in American society.”

California, currently home to almost one-third of America’s English-learner students, is a particularly instructive example for thinking about the politics surrounding multilingual instruction in U.S. schools. In an article analyzing the rise of California’s English-only movement, Laurie Olsen, a researcher and EL advocate, argued that a “worsening economy and the increasing ethnic and linguistic diversity of the state provided fertile ground for politicians to build their popularity by feeding on the fears of a shrinking White majority and focusing campaigns about the incorporation of immigrants on the terrain of public school policy.”

In the early 1990s, California’s poverty rate spiked and housing values dropped by more than 20 percent. This at a time when the state’s foreign-born population was growing quickly. Writing in 2007, the University of Southern California demographer Dowell Myers described the dynamic: “Immigrants were a convenient set of outsiders who could be blamed for the unfortunate turn of events because they had arrived on the scene at about the time all the other misfortunes began.” In one 1995 poll, more than 80 percent of Californians expressed concern about illegal immigration, with over 50 percent saying they were “extremely concerned.”

These anxieties led to serious critiques of the effectiveness of California’s bilingual-education programs in raising the achievement levels of participating students. They were ripe targets. Olsen noted that “poorly implemented bilingual programs were resulting in poor educational outcomes for English learners in too many places.”

What’s more, the programs largely operated out of regular view of the state’s native English speakers. California’s programs generally offered Spanish and English instruction to classes of native Spanish speakers until those students were fully proficient in English. As such, they often separated these EL students from their native English-speaking peers. This made it hard for native English-speaking families (and voters) to feel comfortable with—let alone confident in—the state’s bilingual-education programs. How could they believe in a model they knew only as a distant abstraction serving kids who seemed so different from their own?

Against this backdrop, in 1998, 61 percent of Californians voted in favor of Proposition 227, which effectively eliminated bilingual education for English-learning students.

Two-way dual-immersion programs, which instruct native speakers of English and another language in both of those languages, speak directly to some of the old concerns about bilingual education. They customarily start in pre-k or kindergarten, when children’s brains are still plastic, and have not yet learned to be monolingual. Research suggests that new language acquisition generally works best, fastest, and fullest when it begins early.

Two-way dual-immersion programs enroll approximately equal ratios of native English speakers and native speakers of the other language. Historically, reaching this level of linguistic integration has required schools to sell English-speaking families on the benefits of multilingualism, while also reassuring families that speak the other language at home that maintaining their native tongue won’t damage their children’s development of English proficiency.

Two-way dual-immersion programs help English learners continue to develop in their home languages. But some new research suggests that the presence of their native English-speaking classmates might also help them learn English and succeed academically. A recent study of San Francisco’s dual-immersion programs found that these programs were especially beneficial for helping English-learning students succeed in math, literacy, and even in learning English.

Naturally, native English-speaking kids also benefit from regularly talking with peers who fluently speak the other language featured in a given immersion program. This is straightforward enough: If the only native Spanish (or Mandarin, or French, or Arabic) speaker in a multilingual classroom is the teacher, it makes it much harder for students to avoid relying on English. But if the class is full of native Spanish speakers, that should help all students learn to work—and engage socially—in both English and Spanish.

Furthermore, the linguistic integration of these programs can give native English-speaking families more comfort with and interest in multilingualism—and, in turn, multiculturalism—generally. While the old bilingual-education programs served English-learning children separately, in some other wing of their schools, dual-immersion programs bring English-learning students into schools’ mainstream classrooms and convert their home languages into assets for the entire school community.

All of this is making dual-immersion programs easier to sell to a linguistically diverse range of families. In particular, interest from middle-class, English-dominant, cosmopolitan families is helping to drive these programs’ expansion. Becky Reina is a white, native English-speaking mother of two children in one of Washington, D.C.’s dual-immersion programs. In an email, she told me that such models can help reduce the racial and socioeconomic segregation of schools in cities like Washington, whose public-education system still struggles with the aftermath of a white flight that began a half-century ago. Dual-immersion programs, she said, can attract affluent, white students into schools “that have previously consisted of exclusively non-white and largely low socioeconomic-status students.”

Academia Antonia Alonso’s Aviles is finding similar interest from the parents in his school: “We thought that Latino communities were going to be more interested [in our school] because they understand the value of two languages, but we’re finding that lots of English-speaking families also recognize the value of access to a second language.”

Catherine Brown, the vice president of education policy at the left-leaning Center for American Progress, said that her son’s Washington, D.C., dual-immersion school puts a high value on serving different linguistic, racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic communities. “There’s a lot of people who have really thought out this cool, global, culturally complicated learning environment.”

It’s no surprise, then, that communities across the country are looking to start and expand dual-immersion programs. Multilingualism is hot, especially in gentrifying urban areas with shifting populations. Many white, English-dominant families are moving to economically dynamic cities for their promise of upward social mobility, and these cities’ tight housing markets are bringing them into the same areas as linguistically diverse communities of immigrant families. The cities’ school districts are using dual-immersion programs to encourage these new residents to send their children to schools in their own zip codes and to provide equitable educational opportunities for all kids. For instance, Portland, Oregon—the country’s fastest-gentrifying city—says its dual-immersion programs exist to close “the opportunity gap for historically underserved students.”

There’s evidence that this strategy is living up to its promise. A recent study of Portland’s dual-immersion programs found a wide array of benefits for students. By the sixth grade, English learners in these programs were more likely to be proficient in English than ELs in other language programs. Dual-immersion programs also significantly raised all students’ literacy scores in English, and helped students reach an “intermediate” proficiency level in the programs’ other languages (on average). Ongoing research has confirmed those findings.

Dual-immersion seems to be good at everything—for everybody. It’s popular with English-dominant families, it’s good for ELs, it’s effective at promoting integration and multilingualism.

But—and here’s the rub—if a two-way dual-immersion program helps generate middle-class interest in multilingualism, that dynamic could also undermine the program’s design and effectiveness. What happens when rising demand from privileged families starts pushing English learners out of these programs? Advocates for educational equity are already seeing this specific problem play out in their communities.

“Opportunity hoarding [is] happening everywhere,” said Courtney Everts Mykytyn, the founder of Integrated Schools, an organization encouraging white parents to choose to integrate their area schools. She was referring to a phenomenon in which wealthy families wield their influence to secure access to educational resources in ways that crowd out traditionally underserved families. This has sparked the development of “one-way” dual-immersion programs, which also provide students with instruction in two languages but enroll mostly—or entirely—English-dominant children. When a two-way dual-immersion program gentrifies into a one-way program, Mykytyn said, “we’re not talking about integration, we’re talking about what other special programs your white kid can get, your privileged kid can get.”

In other words, if integrated, two-way dual-immersion programs make multilingualism more appealing to English-speaking families, they can also shift these programs’ focus away from educational equity for English learners. Left unchecked, demand from privileged, English-dominant families can push ELs and their families out of multilingual schools and convert two-way dual-immersion programs into one-way programs that exclusively serve English-speaking children. In some places, this ultimately results in a system in which English-dominant students get access to Spanish-English dual-immersion programs, while native Spanish-speaking students are consigned to English-only programs.

Mykytyn explained how that happens. “When something tips to becoming ‘the cool school,’ the cool thing, the next thing you can get for your kid—that’s the problem,” she said. “So individual schools, in order to increase their enrollment in some places, will start a dual-language program with the best intentions. Pretty soon … the privileged kids get more privileges.”

In many cases, this problem stems from cities’ gentrifying real-estate patterns. Most U.S. elementary schools enroll students based on their home addresses. If you live in a school’s surrounding neighborhood, you have purchased the “right” to send your children there. Trouble is, the real-estate market can very easily—and very quickly—put neighborhood public schools’ programs out of financial reach for the families of EL children: Their child poverty rate is about 10 points higher than the poverty rate of English-dominant families. If a two-way dual-immersion program designed to serve equal numbers of ELs and native English-speaking students starts attracting attention amongst other privileged families, that increased demand for houses in the neighborhood can contribute to rising housing costs that push out ELs’ families.

In Washington, D.C., dual-immersion programs are attracting significant demand from English-dominant families. One of the city’s oldest immersion programs, Oyster-Adams Bilingual School, has seen its surrounding neighborhood become so English-dominant (and white and wealthy) that the school is running short on native Spanish-speaking students. Neighborhood students get guaranteed slots at kindergarten, and these are now taken almost exclusively by English-speaking children, so the school has taken to overweighting its pre-k enrollment toward native Spanish speakers, reserving 30 of the 36 available pre-k seats for Spanish-dominant kids. Just 15 percent of the school’s students are classified as English learners. Not coincidentally, just 23 percent of students come from low-income families (across D.C. Public Schools, it’s 77 percent).

Newer immersion programs around the city are also facing growing gentrification pressures. For instance, in the district’s rapidly gentrifying Petworth neighborhood (where I live), the median 2015 price of a three-bedroom house that guarantees a seat at Powell Elementary’s highly regarded dual-immersion program was $649,900. By contrast, the average cost of a home whose location guarantees access to the nearby (English-only) Truesdell Elementary was $450,000.

Lotteries can help ameliorate this problem. When schools enroll students randomly, without considering families’ places in the real-estate market, it makes it difficult for privileged parents to purchase guaranteed access to any particular educational program.

And yet, this is no guarantee that a dual-immersion school will remain insulated against real-estate pressures. The economic pressures pushing many English learners’ families out of a city’s gentrifying neighborhoods can also, eventually, drive them beyond the city limits. Once they’re in the suburbs, in many cases, they’re precluded from applying to enrollment lotteries for the city’s dual-immersion schools.

What’s more, the advantage of random lotteries—they reduce schools’ control over their enrollments—can also be a problem. Lotteries can’t guarantee that dual-immersion programs will enroll students with an even balance of language proficiencies in cities where English-dominant students account for a large (and often growing) percentage of the population. In other words, lotteries can partially stop real-estate privileges from shaping a dual-immersion program’s enrollment, but any linguistic balance will be as accidental as it is unlikely.

What to do when an education model that thrives on integration becomes so popular that privileged families take it over and resegregate?

In theory, the tension here could be artificial. The ability to converse and learn in more than one language is good for all kids. The United States would be better if every student left high school with a multilingual seal on her diploma. The trouble is, at present, the growth of dual-immersion programs is limited by the country’s shortage of teachers who speak a non-English language well enough to use it in class. There simply aren’t enough bilingual teachers to simultaneously meet all ELs’ needs and satisfy growing demand from privileged families. In many communities, demand far outstrips supply: After current students’ younger siblings were offered seats, D.C. Bilingual Public Charter School had just 22 open pre-k slots available this year. There were 675 children left on the school’s pre-k waitlist after the enrollment lottery.

This zero-sum situation means that education leaders who are adding or expanding dual-immersion programming have to make choices. If policymakers open one-way immersion programs to meet growing demand from English-speaking families, it makes it harder for them to open more of the linguistically diverse two-way programs that are maximally effective for English learners.

So: Policymakers could make the training and hiring of bilingual teachers a top priority. They could offer incentives to encourage bilingual college students to pursue teaching. They could develop programs to give bilingual teachers’ assistants and paraprofessionals multiple, flexible paths to becoming fully licensed teachers. They could adjust the country’s visiting-teacher visa program (the J-1) to provide more of these educators a path to long-term work permits and U.S. residency options (most currently have to leave after three years).

But in the meantime, leaders will be stuck with tough choices over where to open dual-immersion programs—and for whom?

State policies can help ensure that ELs get equitable access to new—and existing—multilingual-education programs. To that end, some states have established bilingual-education mandates for districts serving significant numbers of English learners. In states where these programs are well established, like Texas and New York, districts are exploring ways of converting bilingual classrooms into dual-immersion programs. But policies like these are hardly the rule. Most states’ policies for expanding dual immersion are indifferent to whether the programs are two-way and integrated or one-way. The large majority of Utah’s new dual-immersion schools are one-way programs, for instance.

When new dual-immersion programs are established, some local school leaders are setting enrollment policies that are directly aimed at creating a balance between native speakers of English with native speakers of the program’s other language. This can mean establishing two lotteries for a dual-immersion program—one for native speakers of each language. Alternatively, it can mean deciding to place new dual-immersion programs in neighborhoods with large numbers of ELs.

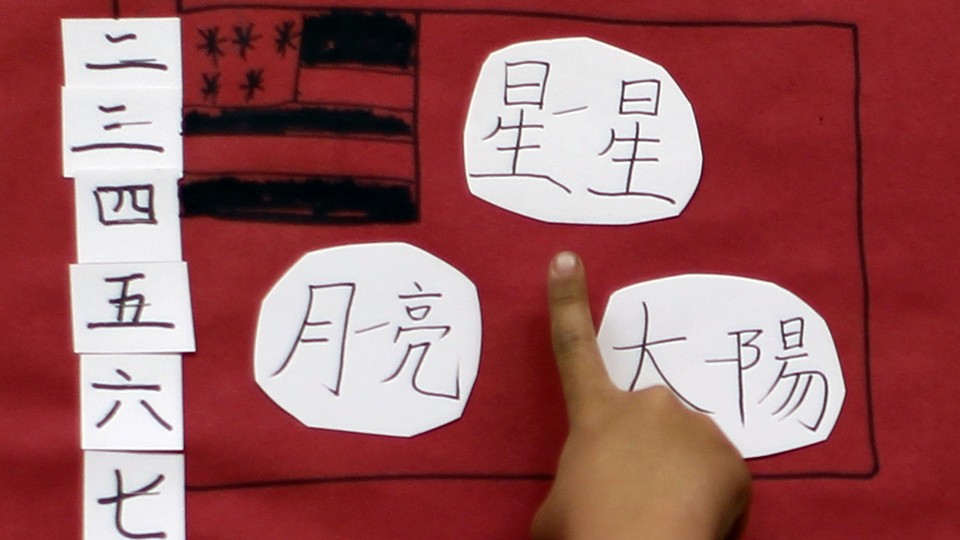

Linguistic integration may even lead to benefits beyond multilingualism and educational equity. At Academia Antonia Alonso, Spanish- and English-language abilities vary throughout the building. Some students use Spanish to talk to teachers and classmates. Others switch to Spanish only for answering their teachers. Still others listen and understand their teachers’ questions in Spanish before answering in English.

School leaders say this balance builds an environment where all students are experts in something and developing in others. As students learn to rely upon the linguistic strengths of their peers, it can help them be more open-minded to other ways that classmates may have different backgrounds or needs. In one Antonia Alonso classroom, for instance, a student with special-developmental needs has organically developed into a teacher assistant, calling out Spanish directions in a foghorn voice and leading her peers in chants. Her behavior initially seems out of place—but her classmates’ enthusiastic responses make it clear that it works for their class.

The diversity of linguistic strengths also creates a special dynamic between students and their teachers. While students are learning—and learning in—both languages, not all of the staff are fully bilingual. This means that, for instance, English-dominant teachers are learning to recognize their Spanish-dominant English-learner students as experts. “It’s amazing,” Aviles said. “[The students] can see themselves in us, the teachers, learning with them.”