Meet Mauricio Peña, a Chicago reporter who has covered the Southwest Side and migrant farmworkers in Southern California. At Chalkbeat, Mauricio will be covering Chicago Public Schools. Below is his introduction to our readers.

When I was a child, adults often had my siblings and me translate for our immigrant parents.

We were still learning English ourselves, and it felt as if we were carrying the weight of the world trying to make sense of conversations before explaining those words effectively in another language.

From casual translations at grocery stores to more serious visits at clinics, or explaining school notes, rules or policies — something my parents simply weren’t familiar with — it felt daunting and often stressful.

Until fifth grade, my school district didn’t consider me fluent in English, a fact I didn’t learn until reading a college recommendation letter from a school counselor years later. So I would be pulled out of class for extra help on the one hand, while also helping translate for my parents’ conversations with school officials on the other.

Even as a child, I recognized the dissonance between being labeled needy while shouldering a responsibility that belonged to district officials.

In Mexico, my parents attended elementary school until leaving to work as farmhands. When they arrived as young adults to California’s Coachella Valley, they found work as farmworkers, gardeners, restaurant workers, and housekeepers. Survival was their priority. All they asked of their children: work hard and don’t get into trouble at school.

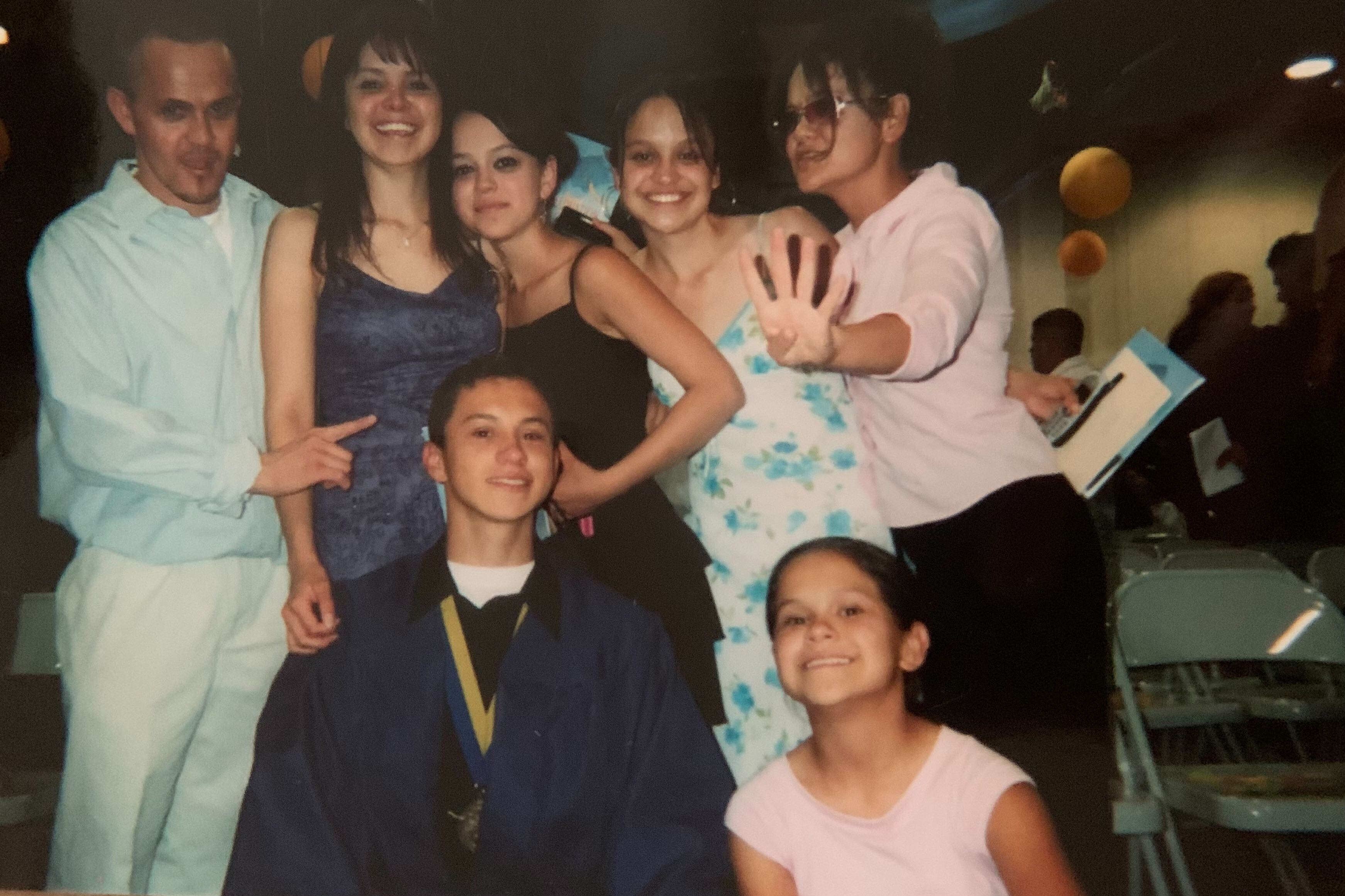

For me and my six siblings, taking on the task of helping our parents navigate our school experience and other responsibilities of living in the U.S. meant growing up earlier than some of our peers.

Our experience is far from unique.

In my seven years of reporting on Chicago’s Southwest sides and rural migrant farm working communities in Southern California, I’ve met many new immigrant families that share my family’s experiences.

The parents became essential workers who immigrated dreaming of a better life for their families. Part of this dream is seeing their children pursue a higher education. That’s a heavy responsibility for any child to carry during normal times — and perhaps an impossible burden during a crisis when rules and regulations are constantly changing.

Since the start of the pandemic, I’ve thought many times of how difficult it must be for English language learners trying to navigate remote learning. Staring at a screen for hours trying to absorb information in another language is tough enough — then add trying to understand the ever-changing information from city and district officials on whether they’ll be returning to school in person the next day.

At Chalkbeat, I plan to report on how English learners have experienced the pandemic and remote learning, what they need academically and emotionally, and what resources are available for them. How are schools using federal aid money to help these students make up for any learning loss? Is the help reaching those most in need?

I’m eager to hear from readers about what stories you’d like me to prioritize. Please don’t hesitate to email me at mpena@chalkbeat.org or message me on Twitter @mauriciopena.