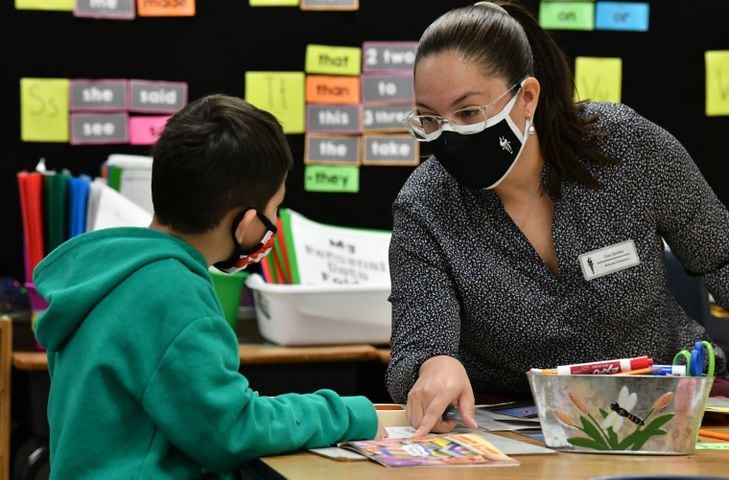

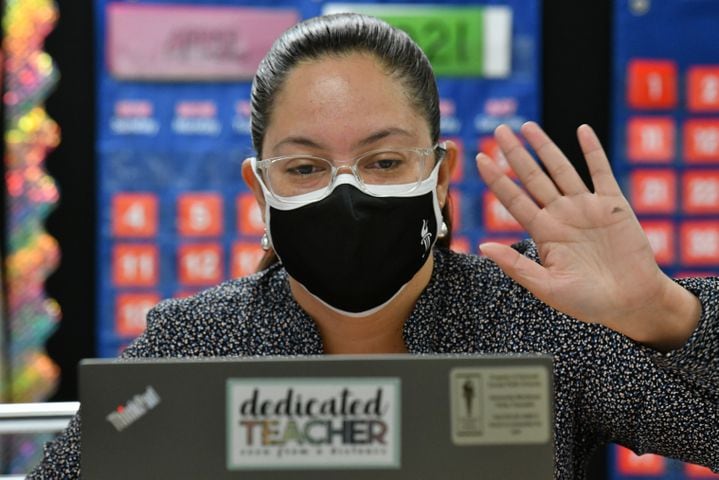

Lies Toribio walks into a classroom at Bethesda Elementary and sits in front of a laptop bearing a sticker: “dedicated teacher.”

Toribio, 41, teaches kindergartners in person and virtually, a challenging feat for someone in her first semester as a full-time teacher. But she’s jumped bigger hurdles at the school near Lilburn, where she was first hired 11 years ago — as a custodian.

“You always work with love and pride, no matter what you do and what profession you are,” Toribio said.

The career transformation is a dream come true for Toribio, who earned an education degree in the Dominican Republic and taught briefly there before immigrating to the United States to join family in Lawrenceville.

She knew little English when she moved to Georgia, preventing her from pursuing a teaching certification here. She worked different retail and cleaning jobs before Gwinnett County Public Schools hired her in 2010 as a custodian at Bethesda.

“I fell in love with the environment and the wonderful staff,” she said.

When her co-workers discovered she had a bachelor’s degree in education, they encouraged her to apply for a clerical position in the main office, where she could answer phone calls from the school’s many Spanish-speaking families.

Toribio clerked for less than a year in 2011, until her position was eliminated amid the fallout from the recession. For the next three years, Toribio worked customer service in retail.

Then an assistant principal reached out because Bethesda Elementary needed a paraprofessional to work with kindergarteners in the Spanish dual language program. Toribio got the job and was promoted five years later to work in small groups with older dual language students.

“I learned more about how I could help those students to reach higher knowledge and seek their true potential, all while I was realizing my own,” Toribio said.

When Principal Katrina Larmond came to Bethesda last school year, she was shocked to learn that the woman working with students and translating for teachers had once cleaned her office.

“She has the best personality,” Larmond said. “She was willing to help anybody who asked.”

Every Monday, Larmond emails a morale-boosting quote to staff. One day last fall, the quote was, “Believe in your heart that something wonderful is about to happen. Faith will make it possible. Purpose will make it work. Passion in your heart will make it worth living.”

Toribio read it and decided to tell Larmond about her dream: to become a full-time teacher, although her English is still not perfect.

“I want to be perfect, but perfection is not true,” Toribio said. “If I wait to be perfect, I was never going to be a teacher, because everyone struggles in something.”

Larmond supported Toribio’s goal, and so did the other teachers, who helped her study for the certification exam and brought her resources.

“She is really hard on herself about her language barrier, but when I see all those kids in the classroom, it does not impede the instruction that takes place,” Larmond said. “It does not impede her communication with parents.”

Toribio came into Larmond’s office in November to say she passed the certification exam on the first try. It was late afternoon and the students had gone home. Larmond, overjoyed, shared the news on the public address system. The building resonated with staffers’ cheers.

The plan was for Toribio to start teaching next school year, but the same month, a kindergarten teacher resigned. Larmond decided Toribio would take over after winter break.

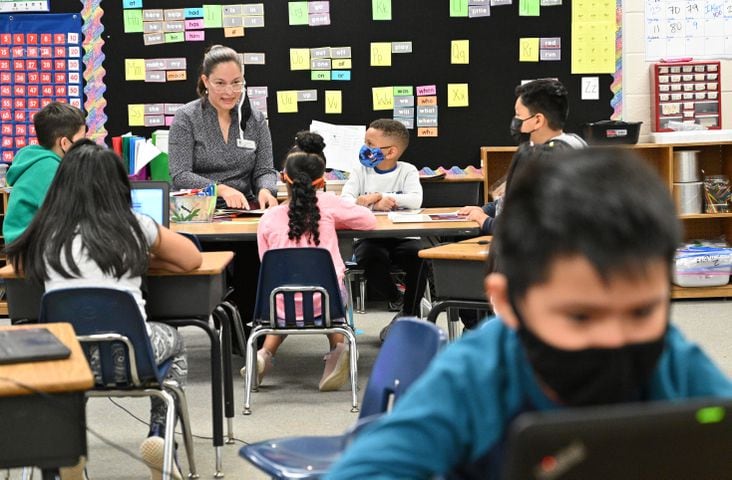

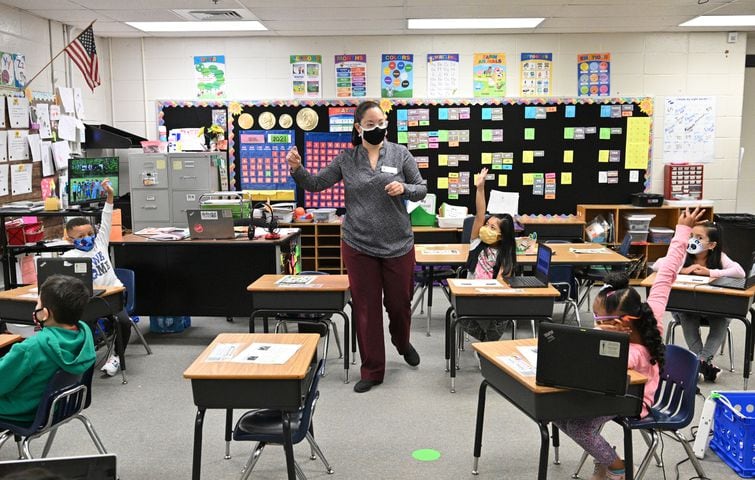

The class was lagging academically and many of the students could not read, Larmond said. But now, Larmond said, Toribio’s students are now the highest performing kindergartners in the school.

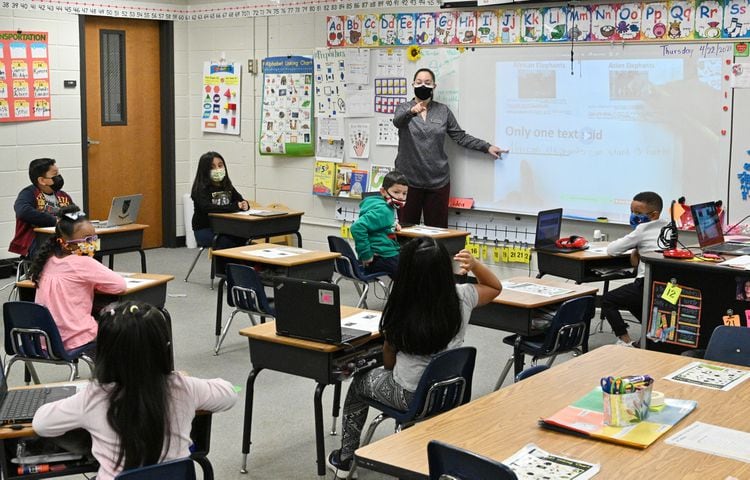

Toribio’s classroom walls are festooned with colorful vocabulary words, numbers, shapes and colors. A dry-erase board on the coat rack proclaims: “In this classroom you are loved, you are important and amazing.”

On a recent day in her classroom, a dozen students were sitting at desks with laptops, spaced apart, while several more tuned in online.

“It is time to go to our reading center,” Toribio told the students.

She said good-bye to her digital students, who read independently while she convened four others around a table in the classroom. Toribio asked her small group for the setting of their story.

“If you don’t know a word, you can look at the picture and look at the words, and you can see everything matches,” she said.

While reading “Caterpillars for Lunch,” Kimora Jiles said Toribio was “the best teacher.”

“When we need help, she help us,” the 5-year-old said.

About the Author