‘They’ve been through so much’: Ferris High School’s Afghan students strive to navigate life as teenagers and refugees

Imagine trying to learn a new language while worrying whether your cousin is still alive, or if your brother’s family has enough to eat.

It’s enough to keep you up all night, especially when your loved ones live half a world away and your only connection is an occasional text.

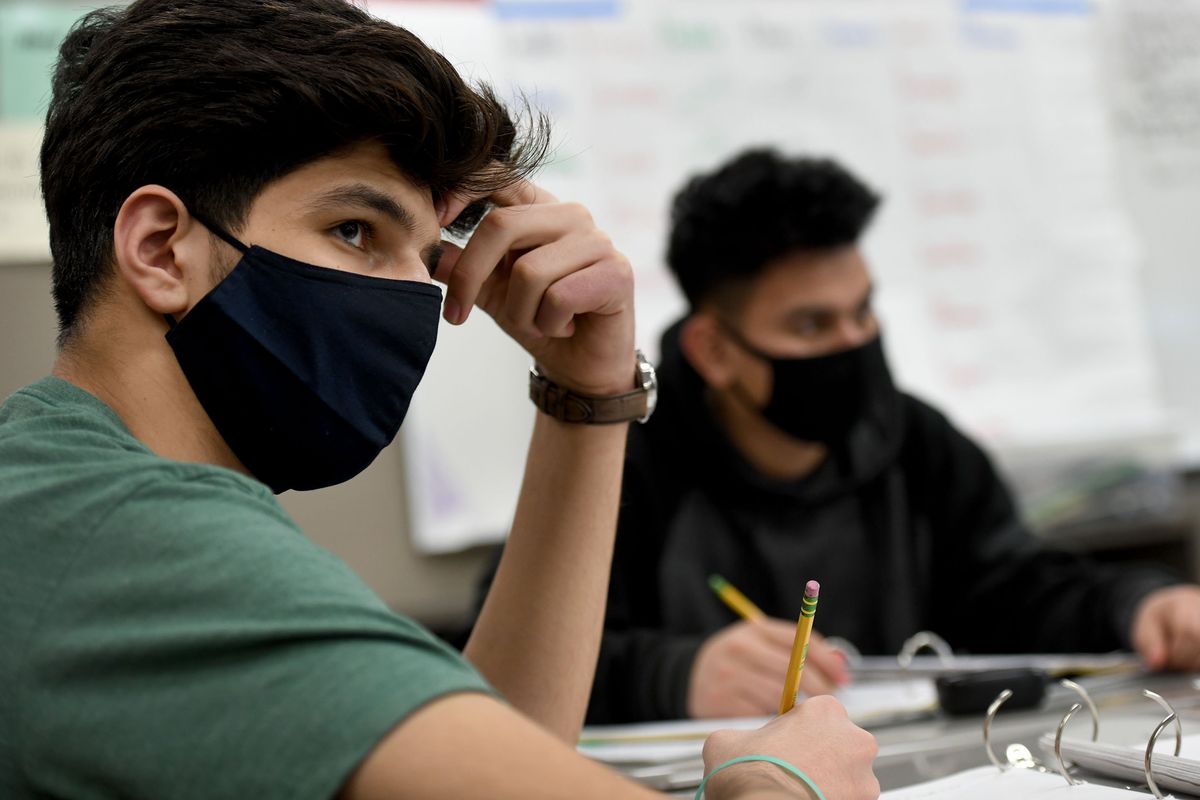

It’s no surprise, then, that a few heads are nodding the next day in Tory Rouse’s classroom at Ferris High School.

Rouse understands.

For three decades, Rouse has worked in the English Language Development program at Spokane Public Schools. Many of her students are refugees, the latest only a few months removed from the crisis in Afghanistan.

Nineteen-year-old Popal Wafa fled Kabul last year with seven other family members.

“It was no good,” Wafa said. “We are happy here.”

Not everyone was that lucky. One of Rouse’s students was orphaned last summer.

That crisis isn’t over. Most of Rouse’s students still have relatives back home, and every night the questions invade their sleep: Is my cousin being hunted by the Taliban? Are my nieces allowed to attend school anymore?

Hence the tired eyes.

Those who made it out are emotionally torn between their new world in Spokane and the old one. Yet they must work to build a new life, and among its foundations is the English language. Yet like America, it’s nothing they’ve ever seen.

After all that, imagine learning a new language so different from your own that you must now write in a different direction.

“Most have adapted pretty well,” Rouse said last month. “They’re working hard, getting used to the different time zones and the different pace of things. But as far as the language, it’s really hard to train your muscles to go the other way.”

“Even picking up their notebooks to take notes, it’s very exhausting, and then there’s the stress of having left their country in less-than-ideal circumstances,” Rouse said.

As Taliban forces took over Afghanistan and closed in on the capital, Kabul, last summer, thousands of Afghans desperately sought refuge in the United States.

Many came to the Pacific Northwest to join relatives already here. According to census data from 2019, about 6,000 people born in Afghanistan lived in Washington.

More than 3,000 have arrived since the upheaval in September alone.

They came with varying levels of education. Some, especially those who lived in cities, attended school fairly regularly, while others, not at all.

Having served refugee students for decades, Spokane Public Schools has a comprehensive program.

The district-adopted curriculum, called Reach, is designed for grades K-5 with support for varying levels of language acquisition.

Middle school multilingual English learners are placed in a grade level by age, and an assessment offers a guide on where to place the student. Some are served by the Newcomer Center at Shaw Middle School.

High school students are initially placed in a grade level based on the total number of U.S. secondary credits completed. High school students who qualify for English language development services are placed in ELD language arts classes based on a placement test.

Students who score at the Newcomer level will be referred to the High School Newcomer Center for placement.

Many are helped by Angela Castillo, an ELD advocacy specialist with Spokane Public Schools.

With the aid of interpreters, her office registers students and eases the path toward what can seem like an upheaval as great as the one they left behind.

“They’ve been through so much trauma, and we understand that,” Castillo said. “When I meet a family, I want them to feel safe.”

“They’ve been through so much, and now they have to go school,” Castillo said.

Many end up with Rouse, who has seen generations of students pass through her classroom at Ferris.

Currently, she has 12 Afghan refugees in the Newcomer program and a few others with higher English proficiency.

The walls of her classroom are covered with dozens of flags – a symbol of work that’s been ongoing since 1992.

“But teenagers are the same everywhere,” Rouse said. “I would say the teenagers around the world are more alike than they are different.”