Tiny Cities Run by Children Inside Texas Schools Are Teaching Social-Emotional and Project-Based Learning — Along With How to Pay Your Taxes

By Bekah McNeel | August 11, 2020

Over the next several weeks, The 74 will be publishing stories reported and written before the coronavirus pandemic. Their publication was sidelined when schools across the country abruptly closed, but we are sharing them now because the information and innovations they highlight remain relevant to our understanding of education.

Corpus Christi, Texas

“I can help the next in line,” says Azalea Arredondo, leaning forward on her elbows and craning her neck to make eye contact with the next customer. He’s busy chatting with the person in line behind him. Arredondo signals again, more urgently, “Next in line!”

The customer, startled, shuffles forward to pay his taxes.

The bureaucratic scene is familiar to anyone who has waited in line for government services — at a DMV or Social Security office, for instance — except for a couple of details.

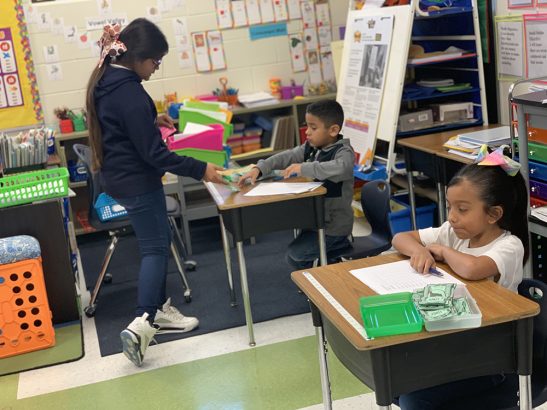

Arrendondo, the all-business “IRS agent,” is in first grade. Her shoulders barely clear the top of the desk, and a giant rainbow-colored bow bounces on top of her head as she swings her legs.

Her customers are third-graders queuing up to pay their taxes in Jaguar Valley dollars (JVD), the currency of Jaguar Valley, a Minitropolis site inside Gloria Hicks Elementary School in Corpus Christi, Texas. It’s one of the newest chapters of a program started in 1996 as an attendance incentive at Sam Houston Elementary School in McAllen, Texas. More than two decades later, Minitropolises have boomed to more than 30 communities throughout Texas and Oklahoma, driven by partnerships with the International Bank of Commerce and other local businesses. During that time, their mission has grown from providing old-fashioned encouragement to show up at school to teaching cutting-edge social-emotional and project-based learning skills.

From 2:00 to 2:45 p.m. every other Friday, Hicks Elementary erupts into activity as the K-5 citizens of Jaguar Valley open up shop. But before they can buy toys, food or books, the responsible denizens must attend to business. They deposit their paychecks, make cash deposits and withdrawals at the bank and, of course, pay their taxes, which brings them to Arredondo’s desk. She and her fellow first-grade agents have alphabetized rosters of each grade with the amount of money each student owes. Once the agent finds the student and collects the taxes, the customer walks away with a receipt, in case of discrepancies.

Arredondo is being paid a salary of her own: an hourly wage in JVD. She’ll get to spend that money in two weeks at the next Minitropolis, and her classmates will man the service desk at the IRS office. Every two weeks roles reverse. Shoppers become workers, and vice versa.

Project-based learning with a community twist

Hicks librarian Andrea Martinez points out that Arredondo’s 45 minutes of tax collection requires several skills not usually combined in a single lesson. As she looks up names, takes bills, makes change and manages her customers, Arredondo is, as John Dewey famously said, “learning by doing.”

“Look how good I am at cutting on the lines,” said one kindergartner in the Jaguar Valley Treasury, where bills are cut and sorted by denomination, building small motor and ordering skills.

The second- and third-graders running small businesses out of their classrooms are ready with a handshake and a “welcome,” while the fourth-graders busily operate the IBC bank and the fifth-graders run the city government.

Proponents of project-based learning say that it draws students into a deeper engagement with the subject matter by letting them see real-world application. Students are encouraged to pursue their interests and look for creative solutions to problems they actually care about.

While most project-based learning springs from individual interests and objectives that align to academic subjects, Minitropolis has a more communal spirit. The entire school works on a single project.

“We’re a miniature community,” said one student at Hicks, explaining the program. “We have to work together.”

Even teachers are required to take on roles in Jaguar Valley. No one takes a planning period or sequesters themself in an office, Martinez said: “It’s about building relationships.”

In Brownsville, Texas, another Minitropolis, at Hudson Elementary, has also created a sense of community, said Principal Rachel Ayala in 2019. Community partners and parent efforts are widely visible in “Hudsonville.” While 94 percent of the students qualify for free or reduced-priced lunch, the school has a closed-circuit television station and a music room lined with guitars and pianos. Parents have built kid-sized picnic tables and Little Free Libraries for Hudsonville as well.

The program is run in partnership with local branches of Laredo-based IBC bank. The marketing department at any IBC branch can reach out to local schools to try to get a Minitropolis started. Once the school’s program is up and running, the branch contributes $1,000 per year to buy basic supplies. The branches also help recruit grocery stores, retailers and other community partners.

In return, IBC earns credits toward compliance with the Community Reinvestment Act, which requires banks to tailor services to the needs of low- and moderate-income communities. Because Minitropolis incentivizes school attendance and teaches financial literacy, it meets those obligations.

First seen as a luxury, then total commitment

Ayala embodies the kind of energetic leadership required to launch a Minitropolis, IBC senior vice president Dora Brown explained: “They have to be a little crazy, the good kind of crazy.”

Brown started the program in McAllen. Not every principal who inherits a Minitropolis has been as enthusiastic, she admitted, but once the program is part of the school culture, they don’t have to be. The teachers, parents, staff, kids and community partners run the show.

It can be a tough sell at first, said Curtis Clark, the IBC marketing manager in Corpus Christi who reached out to Hicks Elementary in 2018. For a campus mired in state requirements and fighting the effects of poverty, adding a Minitropolis might have seemed like a distraction or a luxury item. He had tried for several years to place the program at various Corpus Christi area schools, but administrators were worried about taking on such a complex commitment.

Martinez, the Hicks librarian whose buzzy energy feels similar to Ayala’s, and her former principal finally agreed to try it in the spring of 2019. They intended to launch with two or three in-house shops and no external partnerships except IBC, Martinez explained. Then they traveled to McAllen to see the flagship program. Martinez was inspired by what she saw — everyone was engaged and excited. Kids were taking pride in their responsibilities, and teachers were taking pride in their students.

“When the staff bought in, we just had to go big,” she said.

It was successful enough that when Hicks got a new principal the next year, she agreed to keep it going.

The show-and-tell power of Minitropolis in action has helped the labor-intensive program weather the pressures of No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top and several iterations of Texas’s own accountability system. Although many extracurriculars have been lost to test prep, schools have hung on to the program, Brown confirmed, in spite of its organic, immeasurable nature.

“They are committed to it,” she said.

Around town

IBC has developed a standard rulebook for Minitropolis, but each of the 30 sites has evolved differently, based on the initiatives of school leaders and the local partners they recruit. Some, like the flagship program at Sam Houston Elementary in McAllen, have big-name vendors like Walmart, Target and Home Depot, which sponsor classes and provide merchandise, name tags and uniforms for the elementary school employees.

At Hicks, Texas grocer and education philanthropy heavyweight H-E-B has a mini-grocery store inside one of the classrooms, complete with name tags, shopping baskets and signage. The other vendors sell toys, used clothes and snacks donated by parents.

Hicks students, who prefer to invest in experiences rather than merchandise, can choose from an arcade or a classroom theater, where they can spend the 45-minute period watching part of a feature-length movie.

Those who are short on JVD can go to the “Starbooks,” where students can read or be read to by the store’s employees. The school-based public radio station, which records shows and interviews but does not go on air, plays music so that people can come in and dance for free.

The whole scene can seem a little chaotic, as the halls bustle like a busy street. A fifth-grade police force writes citations for running or yelling and offers commendations when they see helpful behaviors.

“It’s mostly just running,” one officer reported. “You know, kids get excited.”

Even if every student is within the bounds of good behavior, however, there is still a lot of movement and noise.

So that everyone can participate, some of the littlest citizens are escorted by fifth-graders in Hicks’s Future Teachers of America chapter. Jaguar Uber, or “Juber,” also fills in to escort younger kids from room to room. Teachers and aides accompany kids with sensory difficulties or physical disabilities so that they do not miss out.

One of the quietest options, Painting with Jazz, is loosely modeled after “Painting with a Twist,” a franchise that lets patrons drink wine and socialize while they follow along with a painting instructor. For 20 JVD, kids get a canvas and the supplies they need to paint along with the jazz music playing in the otherwise hushed room (no wine, though). The manager offers a polite but muted greeting, and her staff moves quietly between tables, refilling paints and washing brushes for patrons.

Each manager, assistant manager and greeter make different salaries, and all had to apply for their jobs and go through interviews. Now they are in charge of customer service.

The economics of social-emotional learning

“Soft skills” like these are within the scope of social-emotional learning, a growing field that teaches students how to identify and manage their emotions and relationships to others. Organizations like CASEL, a prominent social-emotional-learning think tank, report that employers ask for more training in these skills and are more likely to hire candidates who have them.

Social-emotional learning is a big component of the program at Hicks, Martinez said. In order to participate in Minitropolis, students cannot get into trouble in the two weeks prior. While their peers earn and spend their JVD, students who have lost their Minitropolis privileges go to the library with Martinez for a group conversation about what went wrong and how they intend to keep it from happening again. They talk about ways to keep their tempers under control and to resist bad influences.

Whether it’s the incentive of Minitropolis, or the social-emotional learning happening in the library, Martinez said, disciplinary incidents are down. During the first few Minitropolis days, she said, around 25 students were with her in the library. Ten months later, she only has about four each week, she said.

Mascot monies like the Jaguar Valley dollars have become fairly common ways to incentivize attendance and orderliness. Before the school adopted the Minitropolis program, Hicks was already dealing in school-based currency through its positive behavior intervention system, which rewards students in paper currency for good behavior. Now that behavioral reinforcement is part of Minitropolis. In addition to their Minitropolis jobs, students earn JVD for good behavior and attendance.

Many of the benefits, which now have trendy names and pedagogical movements behind them, come about through the natural workings of the functional community created by Minitropolis, which started as the transactional attendance incentive, explained Brown, the IBC vice president who helped launch the original Minitropolis. The idea was simple: kids would get paid one dollar per day for attendance, with a bonus for every week of perfect attendance. They spent the money once a week.

The first Minitropolis took place on Wednesdays. Once school leaders saw kids’ enthusiasm for the program, they moved it to Fridays. Attendance in McAllen schools was notoriously low on Fridays, Brown explained, as many families travel across the nearby border to visit relatives in Mexico or other parts of the sprawling Rio Grande Valley. Attendance improved as students convinced their parents to delay weekend travel so that they could participate.

Financial literacy for life

The program was effective as an attendance incentive, but Brown said she wondered if Minitropolis could do more, with the right community investment. A strong thread of civic education runs through the program as students interview for their various jobs, run for office, vote, and manage employees, employers and customers.

“Right away, I saw something in it,” she recalled. “It was a training program.”

The elementary school citizens of Jaguar Valley, Hudsonville and other Minitropolises are not just practicing citizenship; they are also training to manage their personal finances.

In one sense, IBC and the other Minitropolis vendors are investing in brand loyalty, embedding themselves in kids’ lives from as early as age 3 or 4. However, in the communities where most IBC branches are located, that may be a good thing.

In McAllen, the poverty rate is 25 percent. In Brownsville, it is 31 percent. Corpus Christi’s poverty rate is lower (16 percent), but 83 percent of children at Hicks Elementary qualify for free or reduced-priced lunch. For these communities, the financial services of banks and credit unions can be a vital help, according to the FDIC.

The San Antonio-New Braunfels metro area has one of the highest unbanked or underbanked rates for major metro areas in the United States, at roughly 36 percent, according to the FDIC. The Federal Reserve of Dallas reported that in the counties along the Texas-Mexico border, 45 percent of the population do not use financial products, such as savings and checking accounts, putting their money at risk and limiting their ability to save for emergencies or future goals.

Microenterprise groups, colleges, and local banks, including IBC, have formed the Deep South Texas Financial Literacy Alliance to reach out to teens and adults. Minitropolis starts that outreach earlier so that when kids get jobs as teenagers, saving is on their minds.

The FDIC recently affirmed the quality of the financial literacy training at Sam Houston Elementary, Brown said. When auditors visited IBC in McAllen, they also awarded a recognition plaque to the Houstonville IBC branch, run by fourth-graders.

The inspectors’ charmed response didn’t entirely surprise Brown, she said. It’s obvious why kids enjoy Minitropolis so much, but it has a similar effect on adults, she explained.

Once they see it, they want to be part of it.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter