Dr. Karen C. Woodson is a recently retired Principal of a Title 1 elementary school serving a significant population of ELLs, as well as a former district-wide EL director of a major school system in the metropolitan Washington, DC area. In this article written for Colorín Colorado, Dr. Woodson describes her school's journey towards equity and school improvement, and how the staff were able to draw upon that journey once the COVID-19 pandemic began in order to ensure that their hard-won successes were sustainable.

In this article, we also include excerpts from a video interview we filmed with Dr. Woodson before the COVID-19 pandemic. All photos are from Dr. Woodson's Twitter feed.

Introduction

Responding to COVID-19

Dr. Woodson and Mother Jones were featured in a July 2020 article from Maryland Matters about how schools serving large immigrant communities were responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the beginning of the 2019-2020 school year, the school I was leading, Mary Harris "Mother" Jones Elementary School in Adelphi, MD, had a lot to celebrate. Mother Jones is a Title 1 elementary school with a significant EL population (what we call a "high-impact EL school.") Of approximately 1100 students, 82% were ELs enrolled in the English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) program in the fall of 2019.

Our school had faced numerous challenges in prior years, yet through transformative change and teacher-led innovation, our team had recently accomplished two major feats:

- improved student outcomes in Reading, Math, and English language proficiency

- removal of the school from the state's comprehensive school improvement list.

This achievement was possible through an EL-centered leadership approach consisting of the following elements:

- an equitable schoolwide English language development (ELD) model

- SMART goals in literacy, math, and language with aligned action plans for each goal

- collaboration in professional learning communities

- teacher-led professional development.

Sustaining equitable access and school improvement during the COVID-19 era

Once the COVID-19 pandemic began and we suddenly transitioned from brick-and-mortar to distance learning in March 2020, I was concerned about maintaining each element of our EL-centered leadership approach, as our students were depending on us to maintain the conditions that set them on a path to improved student achievement. I was also particularly concerned about the impact of distance learning on our equitable schoolwide ELD model, because it was at the core of our school improvement strategy to eliminate variance in the ESOL program and to ensure equitable access to grade-level curriculum for all students.

As I grappled with the COVID-driven adaptive leadership challenge of sustaining an equitable schoolwide ELD model through distance learning, I began reflecting on the journey that brought us to this model, which was finally honed in its third year of implementation. As is the case with any significant challenge, I firmly believed that an examination of past actions could illuminate a path forward.

Part I: Moving Towards an Equitable ELD Model

When I began serving as principal in a Title 1 school serving such a high percentage of English learners, my first priorities were to observe instruction and build relationships with students and staff before instituting any changes. The school was 74% ESOL at that time, with many first- and second-generation immigrant students whose family came from the Northern Triangle of Central America: El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. A number of the families from Guatemala spoke Mam and K’iche.

As a first step, I sought to understand how the school approached ELD instruction for its 657 ESOL students. I was aware that students needed to make sufficient progress in academic English because this was critical to achieving positive academic outcomes for all students in all subjects.

It wasn't long before I was able to determine that the school used a case management approach to staffing its ESOL program, which entailed assigning equal numbers of ESOL students to each of the 12 ESOL teachers across grade levels in order to balance caseloads. Additionally, each ESOL teacher determined the ELD model to use with the students assigned.

For example, ESOL teachers chose among:

- ESOL/ELD instruction or content-based ESOL instruction, both of which may be done on a pull-out, push-in, or self-contained basis

- sheltered instruction in the content areas, where ELD instruction is integrated through the academic subjects. (TESOL International Association 2018 pp. 107-109)

In addition to choosing from among several ELD models, each ESOL teacher made individual decisions about which curriculum to use, and how much ELD instructional time to provide for their assigned groups. In essence, this variance resulted in a lack of simultaneous teaching of grade-level content and academic language. This drove the necessity for an essential question.

It was evident that the case management approach to ESOL staffing, coupled with the lack of coherence and consistency in the ELD model, created a significant level of variance that would stymie our school improvement efforts. Midway through my first year, I posed the following question to the faculty and staff: How can we create schoolwide, equitable conditions for all students to learn grade-level content and academic English simultaneously? In other words, how do we ensure that every student has equitable access to grade-level curriculum by creating maximum flexibility to meet the broad range of needs in our EL and non-EL population?

The answers to these questions would take the faculty on a two-year journey to building an equitable ELD model that was suitable for our specific context. The steps for this journey, and the resources used for each step, are available in this shared document, The Road to an Equitable ELD Model.

While efforts were underway to create an equitable schoolwide ELD model, the school administration worked to establish a collaborative school culture with a school improvement focus by implementing professional learning communities (PLCs) (DuFour & Marzano 2011) in all grade levels and departments. We also clarified the role of ESOL teachers in an effort to address the variance in the school’s ESOL program.

In Cohan, Honigsfeld and Dove (2020), I shared the following vignette about the change in the role of the ESOL teachers:

…we shifted the role of the ESOL teacher to one that focused on creating schoolwide conditions for learning academic English through grade-level content. This meant that two ESOL teachers were assigned to each grade level, regardless of the number of ELs in the grade, enabling them to become experts in grade-level curriculum and full-fledged members of the grade-level PLCs to which they were assigned. Pull-out instruction was limited to beginning level ESOL students. ESOL teachers and grade level teachers deepened their professional learning around differentiation of grade-level curriculum and the provision of explicit content based ELD instruction (pp. 24-25).

Teachers and staff also deepened their professional learning around various collaboration and co-teaching models, as the expectation was that general education teachers and ESOL teachers shared responsibility to create equitable schoolwide conditions for all students to learn academic English and grade-level content simultaneously.

Finally, we created time and space for the school’s ESOL department to form its own PLC to deepen their own adult learning as ELD experts and to address problems of practice related to the development of content based academic English. It was through the efforts of the ESOL PLC that teachers began sharing best practices, conducting book studies, completing Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP) training (Echevarria, Vogt, and Short 2017) and using WIDA resources, such as the WIDA Can Do Descriptors (WIDA Resource Library).

Station Rotation Model: A case study in defining a school's equitable ELD model

At the beginning of our third year, we answered the question posed earlier: How can we create schoolwide, equitable conditions for all students to learn grade-level content and academic English simultaneously? In collaboration with teachers and administrators, the Station Rotation model was our school's response to this essential question. This model, informed by Dove & Honigsfeld's (2018) Multiple Groups model, "… provides students at various levels of English language proficiency targeted instruction to develop their language and literacy skills along with content knowledge." (p. 185) The model also offered maximum flexibility, as "…it can accommodate individual needs in an almost unlimited number of ways." (p. 185)

Teacher-led transformation

Working in summer professional development project teams, teachers were charged to create an equitable schoolwide ELD model that would set all students on a path to continuous improvement by ensuring equitable access to grade-level curriculum. Over time, a culture of teacher-led school improvement developed from:

- their project deliverables

- station rotation models in Reading English Language Arts (RELA)/Social Studies and Math/Science

- the professional development plans needed for the project teams to provide job embedded professional development for teachers and staff on implementation.

This was possible because the professional development topics identified by teachers working in project teams were aligned with our school improvement goals and action plans. Additionally, project teams of teachers were given clear charge statements and project deliverables, which also aligned with school improvement goals and action plans. Since year three was the first year of station rotation implementation, we centered our efforts on implementing station rotations in RELA and Math by building the capacity of teachers and staff to do so.

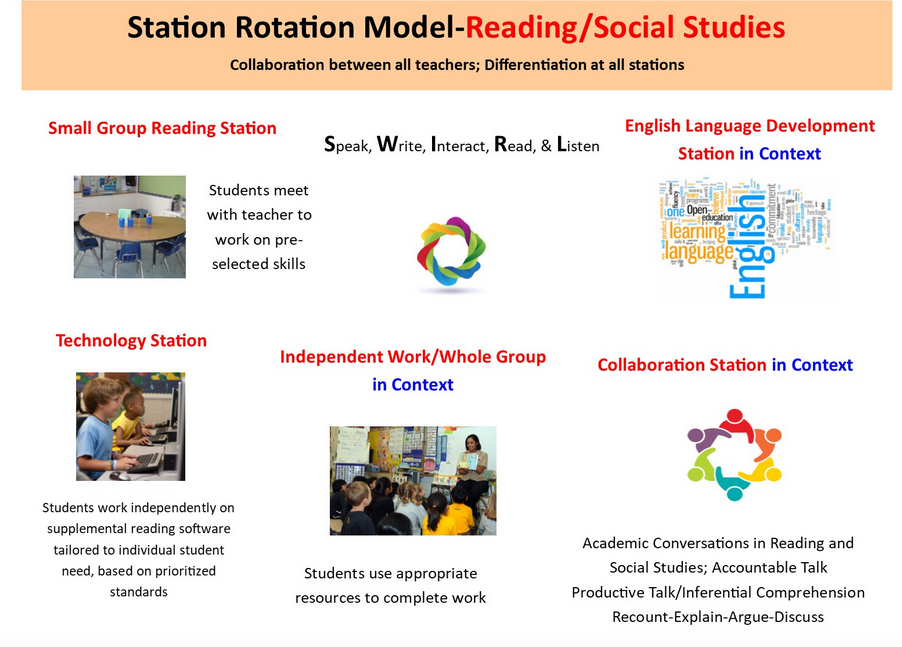

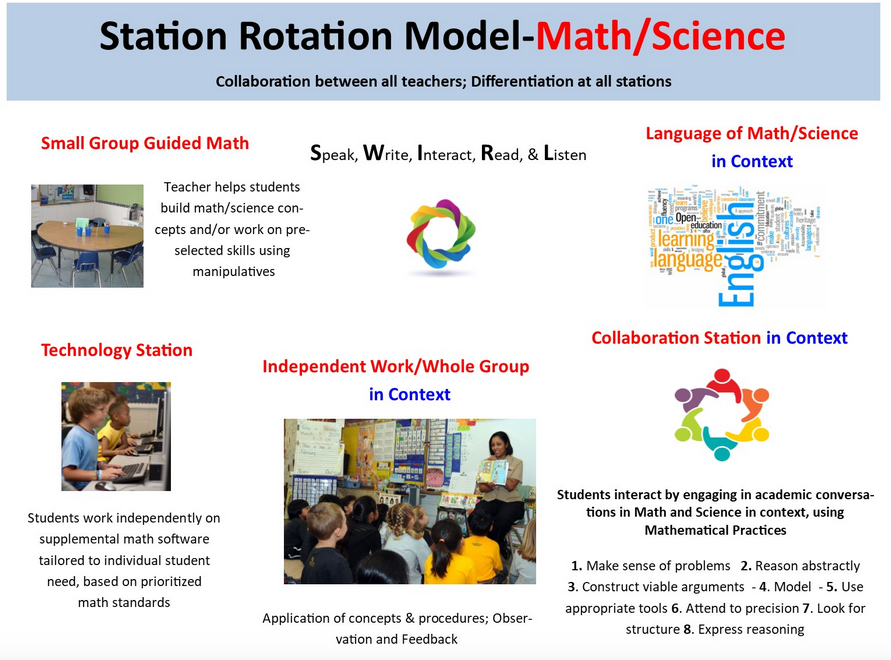

At the beginning of SY 2019-2020, our fourth year, summer project teams adjusted the station rotation models based on extensive feedback from teachers. It was in this year that expectations to implement stations in Social Studies and Science were implemented. The station rotation models for RELA/Social Studies and Math/Science are shown below.

Our station rotation models created equitable schoolwide conditions for ELD to be integrated into the content areas and to ensure that academic content was differentiated for students at varying levels of English language proficiency. In this model, content-based ELD instruction occurred in the RELA/Social Studies ELD station and the Language of Math/Science station every other day. ELD instruction also occurred in the RELA/Social Studies and Math/Science collaboration stations, in context, on alternate days when ELD was not occurring.

This meant that the content areas of RELA and Social Studies and Math and Science were used by the ESOL teachers to design ELD instruction so that language lessons were heavily steeped in grade-level content. In the ELD and Language of Math/Science stations, ESOL teachers designed activities, tasks, and assignments in context that enabled students to learn the features of academic English, as specified by the language objective.

Collaborating on behalf of ELs

In the collaboration stations, ESOL teachers designed activities, tasks, and assignments in context that enabled students to engage in academic conversations using focused listening skills to:

- create and pose ideas

- clarify ideas

- support ideas

- evaluate, compare, and choose ideas (Zwiers & Hamerla 2018 p. 11).

The general education teacher was responsible for delivering differentiated instruction for the small group station, the technology station, whole group instruction, and the independent work station. The classroom teacher was also responsible for ensuring that the ELD station and the collaboration station were running at all times, regardless of the physical presence of the ESOL teacher. This meant that the ESOL teacher was expected to design activities, tasks, and assignments that small groups of students could complete as a team with or without teacher direction.

Staffing considerations

The rationale for student-run stations stems from ESOL staffing limitations. For example, in a high EL-impact school with an enrollment of nearly 1100 students, it would take 39 ESOL teachers to assign 1 ESOL teacher to every classroom for the entire day. Our school had 12 ESOL teachers, so we focused our efforts on creating schoolwide conditions for all students to learn academic English and grade-level content simultaneously by assigning two ESOL teachers at each grade level, Kindergarten through grade 5. We accepted the reality that ESOL staffing would never reach the levels needed for us to assign an ESOL teacher to each classroom at all times. Therefore, we centered our efforts on supporting collaboration and co-teaching relationships in PLCs because without these relationships, it would be impossible to create equitable schoolwide conditions needed to sustain academic growth for all students in all subjects.

Collaboration and co-teaching in a station rotation model necessitated the full functioning of all four components of co-teaching: Co-planning; co-delivery, co-assessment, and co-reflection (Dove and Honigsfeld 2018). ESOL teachers and general education teachers co-planned daily in their grade level PLCs, and jointly identified content objectives aligned to college and career readiness standards, and language objectives essential to meeting those standards. They also collaboratively developed daily exit tickets which were aligned to content and language objectives. Doing so enabled all teachers to assess for understanding on a regular basis. Grade level PLCs utilized: SIOP features (Echevarria, Vogt, and Short 2017) and WIDA resources to differentiate academic content for students at varying English language proficiency levels (WIDA Resource Library), such as the:

- WIDA Can-Do Descriptors Key Uses Edition

- WIDA Features of Academic Language

- WIDA Performance Definitions and WIDA Interpretative rubrics

At the same time, I met regularly with our ESOL lead teacher and the ESOL department chair on a weekly basis. They brought forward information and questions, as well as learning objectives because they were responsible for the ESOL professional learning community in the school. The ESOL team also came together on a monthly basis for full-day professional learning days to continue building their practice.

Continuous improvement through teacher-led learning

According to DuFour and Marzano (2011), school improvement requires a commitment to building the collective capacity of the staff to meet the challenges faced by teachers and staff in meeting student needs. They argue that professional learning must be:

- ongoing

- job-embedded

- aligned with school goals

- centered on improving results

- viewed as a collaborative, collective effort.

DuFour and Marzano contend that

…the best strategy for improving schools and districts is developing the collective capacity of educators to function as members of a professional learning community — a concept based on the premise that if students are to learn at higher levels, process must be in place to ensure the ongoing, job-embedded learning of the adults who serve them. (p. 21)

Accordingly, we developed and administered annual end of year surveys to collect anonymous feedback from teachers and staff on the implementation of the following components of our school improvement plan:

- Collaboration and Co-Teaching: Our Co-Teaching Station Rotation Reflection survey was created based on Honigsfeld and Dove's Integrated Teaching for English Language Learners Observation/Reflection Tool (2018). Teachers and staff reflected on the current state of their co-teaching relationships, as it related to integrating the language and content needs of students in the station rotation model.

- Equitable schoolwide ELD model: Our ELD Across the Curriculum survey was developed to collect feedback from teachers and staff about various aspects of the ELD model implemented in the school.

- Station Rotation Model: Teachers and staff provided feedback on the implementation of small group stations, technology stations, independent work stations, collaboration stations and ELD stations in RELA and Math by completing our Station Rotation survey.

- Professional Learning Communities: Teachers and staff provided feedback on characteristics of PLCs, such as shared and supportive leadership, culture of collaboration, collective inquiry and learning, and mutual trust and respect via our 'Assessing the Characteristics of Your PLC' survey.

Each year, the above feedback from teachers, containing both quantitative and qualitative data, was analyzed to inform adjustments to the four components of our school improvement plan bulleted above. The analysis was then used by teacher-led summer professional development project teams to design and deliver the job-embedded adult learning critical to supporting the implementation of these priorities for the following school year. This continuous improvement cycle of plan-do-study-act turned out to be "pandemic-proof," as it could be easily be sustained through online meeting technologies.

Part II: COVID-Driven Adaptive Leadership

Our new normal started this past spring, just as it did just about everywhere, during March in an abrupt twist of fate when I was given less than 24 hours to prepare students and staff for the historic closing of schools due to the sudden emergence of the coronavirus pandemic.

Our last day of in-person instruction was March 13, and for the next 3 ½ weeks, we focused on checking in with students and families, accepting make-up work from students to close out the third quarter, and preparing online lessons for the 4th quarter. We also distributed Chromebooks to students and ensured that teachers and staff completed district-sponsored mandatory online training on distance learning technology.

And then on April 14, our entire school community jumped headfirst into unchartered waters by beginning 4th quarter instruction in a distance learning environment. The historical significance of this shift did not go unnoticed, and as a faculty and staff, we realized that we were in the midst of arguably the most significant adaptive leadership challenge of our careers, as there were no quick fixes or magic bullets to ease our shift to what would become our new normal.

Rising to the COVID adaptive leadership challenge

We were fortunate to have a strong foundation as we entered this shift. The collaborative relationships built between ESOL teachers and classroom teachers working in grade-level PLCs continued to flourish in the distance learning environment, without interruption. Grade-level PLCs maintained daily co-planning, which was critical to enabling our teachers to continue the effective differentiation of core academic content for students at varying levels of proficiency in English.

Challenges in ELD instruction

However, the impact of the shift to distance learning altered our station rotation model by making it impossible to continue the collaboration station, where students were expected to practice speaking skills by engaging in academic conversations. While a breakout room on Zoom could have supported the creation of the collaboration station in a distance learning environment, there was concern about how that station would run if the ESOL teacher could not be present. The idea of students running the station in the absence of the ESOL teacher raised security concerns that we were ill-equipped to address at the time. Additionally, the ELD station was challenging to implement on a regular basis, as elementary ELD instruction was excluded from the district's distance learning schedule. The unintended result was that it relegated ESOL teachers only to supporting differentiation of academic content.

While we were not agile enough to re-design the collaboration station and fully schedule ELD instruction prior to the end of school year 2020, the end-of-year feedback we received helped inform how academic conversations and ELD instruction could occur in a distance learning environment for school year 2021. Without these critical stations, student achievement is at risk, since students would no longer receive the equitable support critical to learning grade-level curriculum and the academic English needed to access it.

The good news is that the established teacher-led school improvement culture enabled us to capitalize on our annual practice of organizing teams of teachers working in summer professional development project teams to tackle this challenge. In this year of Covid, the feedback received from staff was instrumental in framing the charge statement and project deliverables for the summer 2020 ELD project team, which is the team of teachers identified to address the challenge of restoring the ELD and collaboration stations for school year 2021. With support from school leadership, this experienced project team of teachers was budgeted 10 days to use their expertise to continue leading the school improvement journey by identifying the outcomes and training plans for job embedded PD to bring the equitable schoolwide ELD model fully into the virtual environment.

Distance learning: What worked and what didn't

Our other challenges serving students and families during the pandemic fell into two main buckets: using technology to access virtual instruction and the elimination of our ability to provide direct support to families face-to-face.

Challenges in distance learning

Technology access

Families had two options to access virtual learning. They could do so by logging onto the Google classroom via their Chromebook or other device, or they could tune in daily for lessons on television and complete hard copy packets provided by the school system. Families struggled with both options. For example, many parents were unable to access the Internet, due to the cost and/or the difficulty in filling out forms and providing the documentation needed to access low cost Internet services. Also, helping parents who had little or no literacy in their native language log into a Chromebook with a username and password without being face to face was a significant challenge, even when language was not a barrier. One could give the log-in information, but the parent might not have recognized the letters needed to actually use the log-in credentials. For families to view the lessons broadcast on television, many found it challenging due to lack of cable services, or difficulty getting the stations over the air.

Families had two options to access virtual learning. They could do so by logging onto the Google classroom via their Chromebook or other device, or they could tune in daily for lessons on television and complete hard copy packets provided by the school system. Families struggled with both options. For example, many parents were unable to access the Internet, due to the cost and/or the difficulty in filling out forms and providing the documentation needed to access low cost Internet services. Also, helping parents who had little or no literacy in their native language log into a Chromebook with a username and password without being face to face was a significant challenge, even when language was not a barrier. One could give the log-in information, but the parent might not have recognized the letters needed to actually use the log-in credentials. For families to view the lessons broadcast on television, many found it challenging due to lack of cable services, or difficulty getting the stations over the air.

Reducing in-person family interaction

Finally, the elimination of face to face support for our families was highly impactful in the pandemic-driven shift to distance learning. For example, we were accustomed to frequent events with our families (such as this principal chat) providing equitable support to families with low levels of literacy by filling out various forms and documents on their behalf that were essential to enable them to participate fully in school. For families needing an interpreter, bilingual English-Spanish staff were readily available to support the need to ensure that all families had full access to our services, regardless of their proficiency in English. The elimination of in-person support to parents devastated our efforts to provide hands-on parent workshops that centered on empowering parents to support their students at home by building literacy, math and language skills. We were, however, able to launch our first virtual town hall on Facebook Live, which provides a blueprint for how to reinstitute workshops for families.

What worked

Nevertheless, the challenge of engaging our students in the distance learning environment was met head on by teachers, counselors, and parent & community engagement staff who worked diligently to reach every single student. Thankfully, we had several advantages that assisted students in making the shift.

1:1 computing

For example, all students in grades 3-5 were accustomed to working with a Chromebook daily, since the school was in its first year of having achieved a student-computer ratio of 1:1 in grades 3-5. Because these computers were used in all subjects, students were already accustomed to using the devices daily for academic purposes. Students in Kindergarten through grade 2 used a shared classroom set of Chromebooks daily during their computer stations in RELA and Math, resulting in all of our primary students being familiar with using a computer.

For example, all students in grades 3-5 were accustomed to working with a Chromebook daily, since the school was in its first year of having achieved a student-computer ratio of 1:1 in grades 3-5. Because these computers were used in all subjects, students were already accustomed to using the devices daily for academic purposes. Students in Kindergarten through grade 2 used a shared classroom set of Chromebooks daily during their computer stations in RELA and Math, resulting in all of our primary students being familiar with using a computer.

A new Facebook page for families

Also working to our advantage was our new Facebook page, established one week after the closing of schools. Through our interactions with families, we were aware that many of them were already using Facebook on their cell phones. Since Facebook offered automatic translation between languages, it was easy to see that creating a school Facebook page would immediately allow us to engage our families in two-way communication and get them logged into the grade-level groups created on the page. These private grade-level groups, open only to families of students enrolled in the grade level, enabled two-way bilingual communication with all of the educators on that grade level.

Teachers and counselors were able to use these grade-level groups to:

- communicate with families around instructional expectations

- post videos showing families how to log into various portals used for instruction

- provide encouraging communication related to self-care and social-emotional health

- and offer schoolwide activities, such as a spirit week and a dress up day.

It was gratifying to see the families interacting with their teachers and counselors by sharing pictures and stories about their experiences living in our new normal.

A commitment to family and community engagement

Our school counselors and parent & community engagement staff worked relentlessly in their efforts to establish contact with each family. Operating as a coordinated team, they worked with families to encourage regular attendance, identify needs and remove barriers to learning by making referrals for food and medical services, helping families gain access to Internet service, and providing direct counseling support to students. We also strategically targeted bilingual English-Spanish counseling support to students speaking little to no English who were newly arrived to the U.S. from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. This was important, as our newcomers represented the most vulnerable of our ESOL population, often living in small crowded dwellings with limited access to essential services and difficulty navigating life in the U.S.

Many families in high EL-impact schools experienced significant vulnerabilities prior to the pandemic that presented barriers to learning. Acculturation, poverty, trauma, illiteracy, food insecurity, family separation, family reunification, immigration status, high density housing, sporadic access to medical care, and limited access to the Internet exemplify some of the long-standing obstacles that impede access to learning. Now that we are in the midst of a pandemic, these long-standing obstacles have become even more acute because families in high EL-impact schools are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. High EL-impact schools must not overlook the need to intensify efforts to mitigate these barriers during the pandemic because every student must have the opportunity to continue his or her journey to college- and career-readiness.

Looking ahead: The chair-to-stool transition

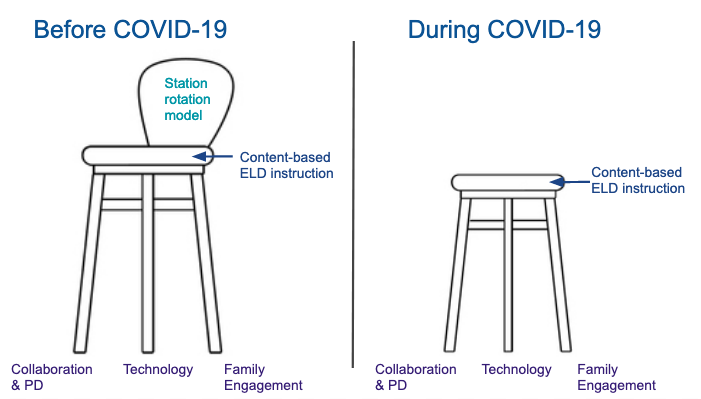

One way to think about our experience is through the following visual. Before COVID-19, our key strengths were our collaboration and job-embedded professional development in PLCs; use of technology; and family engagement. These were the legs of a chair that not only supported the seat — content-based ELD instruction — but made it possible. As we solidified that foundation, we were able to make the chair even more sturdy by adding a strong back — the station rotation model.

During COVID-19, our chair turned back into a stool. At first, we couldn't transition the station rotation model to virtual learning and so the back had to come off of the chair. Yet we didn't lose out on instruction all together because we still had the seat and the legs of the stool. Going into the pandemic with collaboration and the job-embedded professional development in PLCs, use of technology, and strong family foundations made a huge difference in what we were able to accomplish in the spring — all of which better prepared the staff for this challenging year and the question of how to turn the stool back into a sturdy chair.

Part III: Next Steps

It is clear that an equitable schoolwide ELD model creates the conditions for all students to learn grade level content and academic English simultaneously. Leaders in high EL-impact schools must bear in mind that differentiation for ELs is an essential, but insufficient component of an equitable schoolwide ELD model. ELs must also receive content based ELD instruction, if we are to enable them to access grade level curriculum. Differentiation and explicit ELD instruction are required components of any equitable schoolwide ELD model.

Here are some guiding questions to help schools begin to envision their own equitable schoolwide ELD model. I have also repeated below the previously shared link to steps and resources for initiating transformative change towards an equitable schoolwide ELD model.

Guiding Questions to Build an Equitable Schoolwide ELD Model | ||

| Collaboration & Co-Planning | ESOL Level 1 | ESOL Levels 2+ |

| How often do ESOL teachers meet for collaborative planning as a PLC to build their capacity as ELD experts? | How do ESOL teachers provide ELD instruction for beginners, while ensuring access to grade-level content? | How do ESOL teachers and grade-level teachers create equitable conditions for ESOL students to learn academic English and grade-level content simultaneously? |

| How often do ESOL teachers and grade-level teachers meet for collaborative planning as a PLC to focus on the implementation of the school's improvement plan? | How do ESOL teachers and grade-level teachers ensure access to grade-level curriculum for newcomers? | How will all students speak, write, interact, read, and listen to academic English aligned to the content areas? |

| How do structures support daily co-planning meetings for ESOL teachers and grade-level teachers? | How will all students learn the academic English needed for all content areas? | |

| The steps to initiate a journey to transformative change by building an equitable schoolwide ELD model, and the resources used for each step, are available at The Road to an Equitable ELD Model. | ||

Virtual family engagement

In addition to meeting the academic and ELD needs of students in high EL-impact schools, we must continue to find ways to meaningfully engage families and the school community. One tool to do this virtually is to establish a school Facebook page, as described in the previous section, and use it to broadcast live critical information and events that used to occur in a brick and mortar building, such as back-to-school nights and parent workshops.

Critical lessons learned from conducting our bilingual virtual town hall that lend themselves nicely to families and community are as follows:

- Develop a slide presentation that contains the information to be shared in English and Spanish (or any target language) on the same slide. Plan to do the presentation twice, once in English and again in Spanish (or any target language).

- Use a platform that enables the presentation to be streamed live to the school’s Facebook page (or the school’s Youtube page) as it is being presented by school staff.

- Deliver the presentation in English, while having it translated to Spanish (or any target language) via closed caption. If any presenter is a Spanish speaker, be sure to alert the audience and translate the information to English with a voice interpreter. After the Spanish speaker is finished, resume the presentation in English, with translation to Spanish via closed caption.

- Deliver the presentation in Spanish (or any target language), while having it translated to English via close caption. If a presenter is an English speaker, be sure to alert the audience and translate the information being provided to Spanish with a voice interpreter. After the English speaker is finished, resume the presentation in Spanish with translation to English via closed caption.

- Use the Facebook chat window and the Q&A window on Zoom, WebEx, or other online meeting platforms, to interact with families and address their questions in real time.

- Communicate to families the dates and language to be used for the presentation. Explain that the other language will still be used on both dates, but in a closed caption format. This give families the flexibility to choose the linguistic environment that best suits their learning preference.

- Streaming live to Facebook or Youtube creates a recorded archive on your school’s page. Families and community members can revisit the information, in the language of their choice, as their schedules permit and as many times as they wish.

Closing Thoughts

Making the commitment to create the conditions needed to sustain all students in a high EL-impact school on an upward trajectory to college and career readiness in a distance learning environment is arguably the most significant social justice issue faced by ELs in the history of U.S. education.

Whether high EL-impact schools continue distance learning or resume in-person instruction, it is likely that variance in a school's ESOL program, if left unchecked, could be silently hindering school improvement efforts. As described in this case study, attacking the variance in the ESOL program by implementing a leadership approach that has an equitable schoolwide ELD model as its central element, brings about transformative change that can put a high EL impact school on a sustainable path to continuous improvement — a path that can help a school move through the pandemic and beyond. Students in high EL-impact schools need us to guarantee that the pandemic does not put them further behind by exacerbating long-standing academic disparities. We cannot let them down.

About the Author

Dr. Woodson is a retired Principal of a high-EL impact Title 1 elementary school. A veteran in public education with over 35 years of service as a teacher, instructional specialist and district wide EL Program Director, Dr. Woodson holds graduate degrees in Applied Linguistics and has taught a range of courses at the elementary and secondary levels, including reading, Spanish, English as a Foreign Language, and exploratory courses in Japanese, French, Italian and German. Dr. Woodson has also taught graduate courses in Applied Linguistics, English Grammar, Spanish, Foreign Language Teaching Methods and ESOL Teaching Methodology at several major universities in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area.

An expert in second language acquisition and district level program administration, Dr. Woodson's current efforts focus on creating equitable conditions for English learners in schools, English learner centered school improvement strategies, and Baldrige guided strategic planning. Dr. Woodson is also the Founder of Leading for School Improvement, which specializes in EL-centered school improvement solutions for high-EL impact schools.

Comments

Emily Nelson replied on Permalink

Dear Dr. Karen C. Woodson,

My name is Emily Nelson and I am currently a graduate student working towards a masters degree in ESL Instruction and Curriculum at Arizona State University. I first want to thank you for sharing your incredible findings and insight on the situation that many EL students, families, teachers, and administration are facing during the Covid-19 era. Your case study contains such applicable and in-depth content and I imagine that many have found your research to be a great help during this time.

I am currently researching ways that Covid-19 has impacted EL students and am noticing that the overall increase in the use of technology has been difficult for many; especially parents. The idea of creating a Facebook group for parents and teachers to communicate through is incredible. Would you say that the parents who use facebook as a means to communicate with teachers are in the majority, or is there a large amount that still prefer other forms of conveying information back and forth?

Thank you for your wonderful contribution of research to this topic.

Sincerely,

Emily Nelson

Add new comment